Abstract

The millions of farm workers in the Global South are an important resource for smallholder producers. However, research on their labour organisation is limited. This article focuses on smallholder farm workers in Ghana’s cocoa sector, drawing on insights from qualitative interviews and the concept of bargaining power. We review the labour relations and working conditions of two historical and informally identified labour supply setups (LSSs) in Ghana’s cocoa sector, namely, hired labour and Abusa, a form of landowner–caretaker relations, and identify an imbalance of horizontal power. Further, we analyse the labour relations and working conditions of an emerging and formal LSS in Ghana’s cocoa sector: private labour providers (PLPs). We argue that PLPs are likely to address the imbalance of horizontal power between farm workers and smallholders and bring about significant improvements in the working conditions of farm workers. We also assess the sustainability potential and limitations of PLPs and argue that tensions exist. We contribute to the growing horizontal power perspective by providing avenues for research and policy related to promoting sustained labour rights for farm workers in smallholder agriculture in the Global South.

Introduction

While poor working conditions can be found across different global production networks, the agricultural industry is particularly susceptible to social injustice. This is due to the large proportion of small-scale, low-skilled and migrant workers, who often face significant barriers to accessing decent working conditions and fair wages (Barrientos et al. 2011; Thompson 2021; Kissi 2021). In the agricultural sector, different actors, such as lead firms (including manufacturers, processors and traders from the Global North), Global South governments and local actors, address the working conditions of suppliers through various labour standards, ranging from voluntary approaches to hard laws (FAO 2018; ILO 2019).

These labour standards have led to several empirical studies on their impact on labour relations and working conditions in agriculture. According to Kissi and Herzig (2020), previous studies have focussed more on examining vertical solutions (i.e., the role of lead firms from the Global North) than on horizontal solutions (i.e. the inclusion of governments and local actors from the Global South) for addressing labour rights violations (Raynolds 2014; Schuster and Maertens 2017; van Rijn et al. 2020). However, recent studies have begun to consider horizontal solutions to labour rights violations in agriculture (Alford et al. 2017; Gansemans and D’Haese 2020; Louche et al. 2020).

Despite the increase in research from a horizontal perspective, the literature has focussed more on the labour relations and working conditions of workers in a plantation farm context than on those of workers in a smallholder farm context (Kissi and Herzig 2020; Riisgaard and Okinda 2018). Millions of workers on smallholder farms are part of complex global agricultural production networks, yet they remain invisible. These workers are an important resource for smallholder producers in the Global South. Therefore, research on the struggles of workers on smallholder farms in rural areas is crucial (Gyapong 2021; Kissi 2021).

This article focusses on smallholder farm workers in Ghana’s cocoa sector, drawing on insights from qualitative interviews and the concept of bargaining power. We review the labour relations and working conditions of two historical and informally identified labour supply setups (LSSs) in Ghana’s cocoa sector, namely, hired labour and Abusa, a form of landowner–caretaker relations. Further, we analyse the labour relations and working conditions of an emerging and formal LSS in Ghana’s cocoa sector: private labour providers (PLPs). Finally, we critically evaluate the potential sustainability and limitations of PLPs.

Such an assessment is crucial for improving our understanding of how power dynamics within production systems shape labour issues through horizontal power struggles among non-governmental actors of the same class, identity and status (Pettas 2019). Incorporating the horizontal power perspective in our study helps to enhance our understanding of the extent to which workers on smallholder farms in the Global South are recognised and remunerated. This knowledge can contribute to sustainable improvements in agricultural working conditions and labour relations in the Global South (Mohan 2016; Phillips 2011).

We address questions about labour relations and working conditions using bargaining power theory. The literature suggests that workers in the informal sector, including agriculture, are not necessarily powerless (Selwyn 2007). They derive their labour agency from different bargaining powers, including associational and structural power (Gansemans and D’Haese 2020; Riisgaard and Okinda 2018; Thomas 2021). Associational power refers to workers’ ability to improve labour conditions through collective efforts, while structural power refers to the power workers have because of their position in the economic system (Wright 2000).

Ghana, the second-largest producer of cocoa in the world, presents an interesting case due to the presence of more than 800,000 smallholder farmers, who cultivate an average of 2–4 hectares of land (GSS 2014; ICCO 2020). Additionally, Ghana has a strong government presence through the Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD) and its trade policy, which is partially liberalised compared to Côte d’Ivoire, the largest producer, with relatively low numbers of smallholders and a fully liberalised trade policy (Bymolt et al. 2018; Kolavalli and Vigneri 2018). Despite the strong COCOBOD presence, issues of ethical consumption and sustainability in Ghana’s cocoa sector are mostly governed by Global North lead firms through various sustainability initiatives (Barrientos and Asenso-Okyere 2009; Fold and Neilson 2016; Kolavalli and Vigneri 2018). In addition, Ghana’s cocoa sector is characterised by labour fragmentation (Vigneri et al. 2016), many unemployed youths who are uninterested in cocoa farming (Anyidoho et al. 2012) and an increasing number of young farmers who perceive better opportunities outside of cocoa farming and are likely to leave (Amon-Armah et al. 2022).

In the next section, we explore relevant literature on labour organisations on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana and the bargaining power of farm workers on smallholder farms. We then present our qualitative methods for collecting data on smallholder farmers, Abusas (a form of landowner–caretaker relations), hired labourers and other relevant actors. In subsequent sections, we present our results and a discussion on the labour relations and working conditions of various labour forms. Finally, conclusions are presented, along with further research avenues and policy recommendations for improving labour in Ghana’s cocoa sector.

Labour organisation on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana

Labour on smallholder farms in the Global South is mostly organised based on different irregular labour sources, such as communal labour support, landowner–caretaker relations or sharecropping labour arrangement, hired labour and contract farming (Barrientos et al. 2011; Mukhamedova and Pomfret 2019; Oya 2012). Despite the heterogeneity in labour organisation, there are several common elements in almost all agrarian societies. These elements include a clear division of labour (Barrientos 2019; Masamha et al. 2018), gender-based land tenure systems and agricultural roles (Contzen and Forney 2017; Padmanabhan 2007), different classes and identities (Bernstein 2011; Morgan and Olsen 2011), a low wage rate (FAO et al. 2019) and frequent movement into and out of labour arrangements as well as into non-farm activities (Bernstein 2011).

In cocoa production in Ghana, various labour sources are important, including family, hired labour, landowner–caretaker relations, communal labour support, government labour subsidy programmes and private labour. Since 1910, unpaid family labour, hired labour and landowner–caretaker relations have played a significant role in establishing and expanding cocoa production in Southern Ghana (Amanor 2010; Hill 1961). Hired labour and landowner–caretaker relations for managing cocoa farms have traditionally relied mainly on migrant workers (Amanor 2010; Hill 1961; Torvikey 2021; van Hear 1984). Although migrant labour in Ghana’s cocoa sector has decreased due to demographic changes and institutional factors, it still remains relevant for hired labour and sharecropping setups.

Recently hired labourers and sharecroppers consist of both male and female farmers and non-farmers, including landless migrants and non-migrants (Amfo et al. 2022). However, male labourers dominate, as cocoa farming is perceived to require physical strength and is labour intensive (Bymolt et al. 2018). Hired labourers typically perform a variety of tasks, such as spraying and weeding, on a day-labour or piece-rate basis (Bymolt et al. 2018; Vigneri et al. 2016). Landowner–caretaker relations, on the other hand, take the form of an agreement between the cocoa farm owner and caretaker for the use and management of the farm.

In Ghana’s cocoa sector, landowner–caretaker relations are organised as ‘Abunu’ and ‘Abusa’ based on verbal agreements (Amanor 2010; Barrientos 2014). In Abunu, which means to divide into two, the caretaker bears all the costs of production on virgin farmland and shares the income from cocoa sales at a ratio of 1:1 with the landowner. The Abunu sharecropper takes full control over production decisions and benefits solely from other staple food crops intercropped with cocoa. Abusa, on the other hand, means to divide into three. In this model, a fully mature cocoa farm is given to a caretaker to manage for a certain period. The income is shared at a ratio of 1:2, with the landowner taking two-thirds and the caretaker receiving one-third. Here, the landowner is expected to bear all costs of production and to have control over production decisions. There is also another category of caretakers, usually young migrants, who work seasonally on cocoa farms on negotiated terms with landlords, which may not necessarily be Abunu or Abusa.

Since Ghana’s independence in 1957, engendered communal labour support, locally known as ‘Nnoboa’, has provided labour on cocoa farms through verbal agreements to exchange labour with neighbouring farms for weeding, harvesting, pod breaking and other activities (Amanor 2010). However, recent studies have noted a significant decline in the use of Nnoboa due to some members’ opportunistic behaviour, such as not reciprocating the labour exchange or demanding compensation beyond the agreed terms, leading to a lack of trust (Bymolt et al. 2018; Vigneri et al. 2016). For example, some Nnoboa members may demand payment or more labour than they are willing to provide, causing disputes and straining relationships among farmers.

Regarding labour subsidy programmes, the Ghanaian government has been providing support to young farmers and non-farmers to provide labour services since 1989 (Kolavalli and Vigneri 2018). For instance, the Cocoa Diseases and Pests Control Programme has been offering ‘mass spraying’ services to cocoa farmers since 2001 to combat capsids and black pod diseases. Cocoa farms are sprayed 3 times a year against black pods and twice a year against capsids, free of charge. Additionally, COCOBOD’s hand pollination programme, which began in 2017, employs young people to carry out artificial pollination on smallholder farms to boost agricultural productivity.

Beyond the historical and government setups, it is important to note that the emergence of PLPs from rural service centres (RSCs) is a recent development in Ghana’s cocoa production landscape. These RSCs can be compared to small and medium-sized enterprises that offer various services, including entrepreneurial and agronomic training, input and agrochemical shops, access to credit through private cocoa-buying companies and labour service delivery on cocoa farms. The PLPs that have emerged from the RSC model can be seen as a type of formal sharecropping arrangement, similar to Abusa. In this arrangement, the PLP and the farmer each receive one-third of the sales of the harvested beans, while the remaining one-third is set aside for farm management. Production decisions are controlled by the PLP.

Of the labour forms outlined above, we will focus on two historical setups: hired labour and Abusa as well as the emerging PLPs, because of the existence of a relationship between a worker and a farmer. While this article is not the first to review the labour relations and working conditions of hired labour and Abusa (Bymolt et al. 2018; Vigneri et al. 2016), to the best of our knowledge, it is the first to examine an alternative and emerging model, the PLP, through the concept of bargaining power.

Bargaining power of workers on smallholder farms

The notion that informal wage workers in agriculture are not powerless and that they derive their bargaining power from various sources has been discussed by many scholars, particularly in the context of plantation work (Gansemans and D’Haese 2020; Riisgaard and Okinda 2018; Selwyn 2007; Thomas 2021). To comprehend how workers on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana may derive their bargaining power, we begin with the concept of labour power sources. As conceptualised by Wright (2000) and Silver (2003), the sources of labour power in the global economy consist of two components: structural power and associational power. Subsequently, Schmalz et al. (2018) extended these power resources to include institutional and societal power. However, institutional and societal power are not relevant in the smallholder farm context because they arise from formal cooperation between workers and other organisations, which is heavily rooted in trade unions and hegemonic structures (Schmalz et al. 2018).

Therefore, we focus on associational and structural power in this study. Associational power is defined as a workers’ ability to improve labour conditions through collective efforts, such as unions and parties, as well as workers’ councils, community organisations and institutional representation (Wright 2000). Structural power is defined as the ‘power that results simply from the location of workers within the economic system’ (Wright 2000, p. 962).

While Wright (2000) contended that structural power may influence associational power, Silver (2003) posited that there are two distinct forms of structural power, workplace bargaining power and marketplace bargaining power, both of which are disruptive in nature. Workplace bargaining power arises from a worker’s ability to refuse to work, while marketplace bargaining power is derived from having rare skills or qualifications that are in high demand by employers (Schmalz et al. 2018; Silver 2003). Associational and structural power concepts were initially developed to analyse bargaining power in the context of formal labour (Silver 2003; Wright 2000). However, Riisgaard and Okinda (2018) adapted the framework to apply it to the informal labour context, particularly smallholder farms, which had not been studied previously (Rizzo 2013; Selwyn 2009).

As union rates are generally low or non-existent for informal workers in Global South agriculture (ILO 2021), Riisgaard and Okinda’s (2018) model includes all modes of engagement, both formal and informal, as well as access to information, information sharing and withdrawal of labour in the analysis of associational power. This adjustment is crucial, as smallholder farmers often rely on informal networks and relationships rather than on formal organisations for access to resources and support. Their model analyses workplace bargaining power based on labour withdrawal, access to information and information sharing and marketplace bargaining power based on smallholder farm workers’ dependence and access to alternative employment of smallholder farm workers (Riisgaard and Okinda 2018).

Given our focus on smallholder farms, we follow Riisgaard and Okinda (2018) in analysing our data. We employ labour withdrawal, access to information and information sharing among cocoa farm workers in both associational and workplace bargaining power analyses, while we utilise cocoa farm worker dependence and access to alternative employment in the analysis of marketplace bargaining power. Overall, both associational and structural power in all forms and contexts are largely a function of the bargaining power of cocoa farm workers (Gansemans and D’Haese 2020; Riisgaard and Okinda 2018; Schuster and Maertens 2017). Our aim is not to examine power differences but rather to understand how horizontal power shapes labour relations and working conditions in Ghana’s cocoa sector (Pettas 2019).

Methodology

Based on insights from qualitative interviews with smallholder producers, cocoa farm workers, LBCs and other relevant actors in the cocoa sector of Ghana and the concept of bargaining power, we review the labour relations and working conditions of hired labour and Abusa. Following the same structure, we examine the labour relations and working conditions of PLPs. The qualitative research method offers an opportunity to explore and explain how horizontal power shapes labour relations and working conditions in Ghana’s cocoa sector.

We conducted fieldwork between May and August 2019 in four major cocoa-growing areas of Ghana: Western North, Ashanti, Ahafo and Bono Regions. These are the largest producing regions and are known for their practice of all the labour forms, particularly PLPs. For each region, we selected at least one district and some villages and towns (Table 1) that are most actively involved in various local labour forms.

In addition, we conducted interviewsFootnote1 in December 2022 to particularly complement the PLP data due to recent changes in its dynamics. This was mainly conducted in Assin Fosu of the Central Region, given the continuous presence of a PLP.

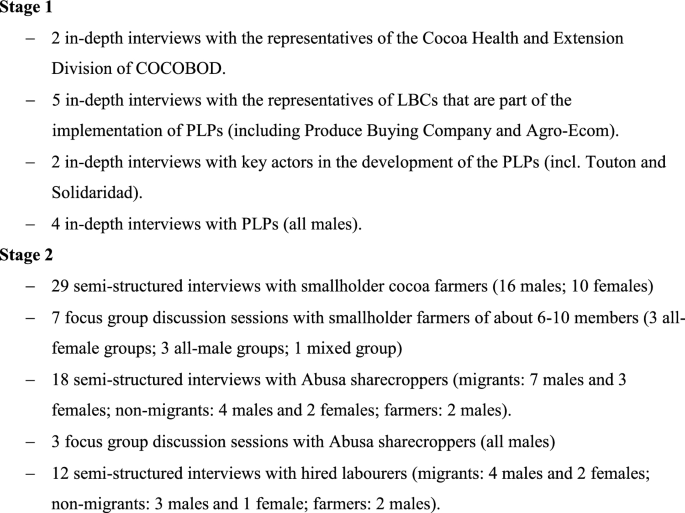

We used purposive sampling to select smallholder producers from various communities and villages that were visited through LBCs. As that there are about 40 LBCs in Ghana, we purposely selected farmers from the top two LBCs, the Produce Buying Company and Agro-Ecom Limited, which together account for more than 40% of internal cocoa bean purchases (COCOBOD 2017). In contrast, we did not have pre-existing information on the availability and accessibility of hired workers, Abusas and PLPs, so we used snowball sampling methods to select a variety of workers. In total, we interviewed 72 different actors and conducted 10 focus group discussions with smallholders and Abusa. We followed a two-stage data collection process, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

We conducted a few interviews in English but mostly used Twi, a dialect widely spoken as a first language in all the cocoa-growing areas we selected for the study. We sought participant consent and gave careful consideration to ethical research issues, including anonymity, confidentiality and convenience. We conducted individual interviews and focus group discussions, which, on average, lasted 45 and 90 min, respectively. We recorded the interviews in the local dialect and then transcribed them into English. Using qualitative content analysis (Lewis 2015; Silverman 2017), we explored how horizontal power shapes labour relations and working conditions in Ghana’s cocoa sector. In summary, we gathered qualitative information from respondents regarding the history, organisation and necessity of various labour forms. We also examined labour relations and working conditions in the context of bargaining power.

Results and discussion

History and organisation of hired labour and Abusa

Since 1910, hired labour and Abusa have dominated the establishment and expansion of cocoa production in Ghana (Amanor 2010; Hill 1961). Traditionally, these forms of labour relied heavily on migrants from the Volta region of Ghana, neighbouring Togo as well as the Northern part of Ghana and neighbouring Burkina Faso (Amanor 2010; Hill 1961, 1997; Torvikey 2021; van Hear 1984). Migrant labourers played an essential role in expanding Ghana’s cocoa production, leading the country to become the world’s number one producer between 1911 and 1976. However, Côte d’Ivoire took over in 1978 and remains the leading producer today (Hill 1961, 1997).

Agrarian capitalism, abundance and easy access to land have historically attracted migrants to invest in land acquisition through their profits from cocoa farming, oil palm farming and non-farm activities in the Eastern region (Hill 1961). However, the number of migrant labourers in Ghana’s cocoa sector has significantly decreased recently due to demographic changes, such as increased education levels, smaller family sizes and migration, as well as institutional factors, such as low wages, inadequate farm land and high farm job insecurity (Anyidoho et al. 2012; Dzanku and Tsikata 2022; LeBaron and Gore 2020). Thus, current hired labour and Abusa setups include both landless migrants and non-migrants as workers.

In our study, we acknowledge the diversity of class, ethnicity and identity that exists among migrant and non-migrant labourers. Migrant labourers are mostly internal and originate from communities outside the farming region (Amfo et al. 2022), with the majority identified in our study being Dagatis, Kusasis and Gurunsis from Northern Ghana and Ewes, Krobos and Akuapims from Southeastern Ghana. In the Sefwi-waiso municipality and Juaboso district, we found additional migrant labourers from the Bono ethnic group from the centre of Ghana, and there are increasing numbers of labourers from Togo in the Adansi-South district. Both migrant and non-migrant labourers possess general farming skills (e.g. harvesting, pest and disease control and weeding) but not necessarily on cocoa farming. Migrant labourers come from agricultural commodity-growing regions and migrate to cocoa-growing communities during their off-seasons.

We found that migrant labourers are often married with children and have lower levels of education than non-migrant labourers. Non-migrant labourers are often single and, on average, have completed senior high school. Additionally, we observed that most non-migrant labourers do not aspire to become future farmers owning their own land. They see cocoa farming as a means of income accumulation to venture into non-farm occupations. Conversely, most migrant labourers aspire to own their own farms. Their aim is often to gain experience in Abusa sharecropping first and then look for old and obsolete farms neglected and enter into Abunu sharing arrangements with the landowners.

The evidence on labour relations from this research is consistent with the reports of other studies that have examined labour issues in Ghana’s cocoa sector (Bymolt et al. 2018; Vigneri et al. 2016). In the hired labour setup, smallholders employ workers through a verbal contract, sometimes in the presence of a witness, to carry out various tasks either on a day-labour or piece-rate basis for a short or longer period of time. On the other hand, the Abusa setup takes the form of a landowner–caretaker relationship, where landowners may be either absent or present farmers or non-farmers, while caretakers, like hired labourers, may also be farmers or non-farmers, including both non-migrants and migrants.

In the Abusa model, a fully-grown cocoa farm is given to a caretaker to manage for a specific period. The income or harvest is shared at a ratio of 1:2, with the caretaker receiving one-third and the landowner receiving two-thirds. The landowner is expected to set aside one-third of their share for input costs. However, hired labourers receive a daily wage of about Ghana Cedi (GHS) 30–100, depending mainly on the type of task and the size of the farm. For example, labourers who engage in weeding and pruning receive higher wages of about GHS 60–100 per day, while those who engage in harvesting, gathering and pod breaking receive about GHS 30–50. Likewise, larger farms may pay less per day overall, as the contractual agreement is likely to be longer. Hired labourers receive their payments either daily, weekly, monthly, at the end of the activity or in some combination. According to a hired labourer in the Ahafo region, for example, “Hired labourers on long contracts often receive an agreed initial deposit of their total payment and the rest during the ensuing task and/or after the harvesting period, while the short-term contract is often remunerated daily or weekly”.

In Ghana, cocoa farming is generally regarded as a male-dominated activity, and the tasks associated with cocoa farming are gendered. Moreover, the tasks that are typically associated with women in Ghana’s cocoa sector, such as harvesting, gathering and pod breaking, tend to be lower paid than tasks assigned to men, such as weeding, pruning, fertiliser application and spraying. This reinforces gender inequality in the industry (Barrientos 2014; LeBaron and Gore 2020).

The findings from our focus group discussions and individual interviews suggest that women and large-scale farmers are more likely to engage the services of hired labourers. As one female farmer in the Western North pointed out, “Most female farmers here do not have the strength that men do, and we no longer have enough family labour as we had some years back. Hence, we engage the services of hired labourers from time to time”. Meanwhile, farmers with multiple farm ownership prefer the Abusa model. This was noted in a focus group discussion in the Ashanti Region by one farmer who said, “In this community and other farming areas, most farmers have multiple farms in multiple locations. Thus, such farmers prefer to arrange with caretakers to manage some of their farms”.

Overall, the evidence suggests that the recruitment process for both hired labourers and the Abusa model is often informal, with either the farmer or labourer making direct requests or announcements through social networks and community channels. In some cases, potential workers may present themselves as available for work. We also found that depending on the task, the farmer may or may not be present to supervise and assist the labourer in both types of labour setups. For example, one farmer we interviewed in the Bono Region reported that they typically supervise and assist labourers with tasks such as spraying agrochemicals, pruning, harvesting and fertiliser application. However, for tasks such as weeding, farmers do not provide any supervision but inspect the work upon completion.

Cocoa labour is not the only source of income for hired labourers and Abusas. Beyond some being farmers, most labourers engage in other non-farm income-earning activities, including off-season migration by hired labourers to the city and other rural areas. As explained by one farmer in the Western North, “Most of the migrant labourers and the youth are engaged in income earning activities, such as Galamsey, mobile money vending, motorcycle transportation business and also often migrate to nearby communities and Kumasi during the off-season to engage in other business activities”.

Despite the importance of hired labour and Abusa to Ghana’s cocoa production, there is evidence of challenges and complexity associated with affordability and sometimes availability, as reflected in the following views. According to one farmer interviewed in the Bono Region, “The use of hired labour has become less popular in many cocoa-growing areas in Ghana because labourers often charge exorbitant prices that we cannot afford”. On the contrary, a sharecropper who also works as a hired labourer and was interviewed in the same region emphasised a divergent view on costs, stating, “The refusal of labourers to work on cocoa farms is due to low wages given the laborious nature of the tasks”.

Bargaining power of hired labourers and Abusas

Based on our assessment of the labour relations and working conditions of the hired labour and Abusas, we argue that there is an imbalance of horizontal power relations between farmers and workers in Ghana’s cocoa sector. In line with the broader discussion on bargaining power, we found that hired labourers and Abusas have limited or no associational and structural bargaining power due to imperfect information and low labour withdrawal opportunities.

For example, since hired labourers and Abusas, whether migrants or non-migrants, move in and out of agriculture and non-agricultural activities, they have no means of accessing and sharing information. Additionally, the varying interests and aspirations of migrant and non-migrant labourers result in an absence of collective efforts to access and share information. Most respondents noted that Abusa and hired workers have limited access to information regarding input resources and premium payments and do not participate in sustainability programmes. These conditions reflect a lack of access to and sharing of information among cocoa farm workers.

Although cocoa labour is not the only source of income for hired labourers and Abusas, the seasonal nature of cocoa work makes labour withdrawal a non-option strategy for negotiating for better working conditions, particularly for migrant workers. Migrant hired labourers often lack immediate alternative employment opportunities in cocoa-growing areas. As one migrant hired labourer in the Ashanti region pointed out, “Most labourers migrate from far to cocoa-growing areas during the main season from October to May to work as labourers on the farm”. Therefore, the ability of migrant labourers to withdraw their labour is limited, resulting in a power imbalance in labour relations in the cocoa sector of Ghana.

Interestingly, we identified some differences in bargaining power for both migrnat and non-migrant Abusas based on the location of landlords, particularly regarding associational power. For example, we found that Abusas managing absentee owners’ farms hold some level of bargaining power over managing the farms of owners that are present in the community. This stems from control of production resources and access to programme attendance and information. As one Abusa noted during a focus group discussion with Abusas in the Western North Region, “If landlords do not live close to the farming community, caretakers often get the chance to attend cocoa farmer group meetings and have control over production and marketing decisions to some extent”.

Overall, our findings suggest that there is an imbalance of power between cocoa farmers and their migrant and non-migrant workers, which is due to imperfect information and structural barriers, such as class and identity. As a result, workers in the informal and traditional labour supply setups in Ghana’s cocoa sector have limited bargaining power, which makes it difficult for them to negotiate for better working conditions (Carswell and Neve 2013; Coe and Jordhus-Lier 2011). This power imbalance could lead to rising inequality between workers and smallholder farmers and potentially exacerbate the low labour supply in the cocoa sector. Moreover, this finding reflects existing evidence of labour exploitation in Ghana’s cocoa sector (LeBaron and Gore 2020).

History, organisation and bargaining power of PLPs

Considering the challenges, complexities, and the horizontal power imbalance associated with hired labour and Abusa, several actors began pushing for the adoption of PLPs in 2015 to complement informal labour setups. Our interviews revealed that a private company called EMFED FARMS began providing labour services to smallholder cocoa farms in the Central Region of Ghana in 2012, and their success led to several actors, including Solidaridad (an international civil society organisation from the Netherlands), Touton (a cocoa trader), Produce Buying Company (a cocoa licence buying company in Ghana) and the Mastercard Foundation, actively cooperating with private actors, such as EMFED FARMS, to operate more PLPs in the Ashanti, Western North and Bono regions through the RSCs described above. Although Touton referred to these private actors as ‘franchisees’ under the RSCs, there is no officially agreed-upon name for this model, so we refer to them as PLPs.

In this model, a PLP provides management services to an established cocoa farm on behalf of a smallholder farmer for about 5 years through a formal contract. The contract is signed by both the PLP and the farmer, and witnessed by a third party. In case of disagreement, a sub-committee set up by the district assembly resolves the situation. PLPs are often business people who come from farming communities and are either farmers or non-farmers.

The PLP primarily hires male labourers and sometimes female labourers who live in the farming communities and invests in the agronomic capacity development of the workers. This includes offering workers training in their basic rights and responsibilities on the farm. The labourers are a mixture of farmers and non-farmers, mostly between the ages of 18 and 35. As explained by one PLP operator in the Western North, “The PLP concept does not recruit migrant labourers but hires workers trained on agronomic practices from the community—and where workers are inadequate in some farming communities, excess workers trained from nearby communities are employed”.

The main role of the PLP is to pre-invest in input costs (including labour, fertiliser and chemicals) and manage the farm to improve productivity. Farmers are required to honour the terms of the agreement and be present during the harvesting and marketing of the produce. Smallholder farmers pay the PLP through the landowner–caretaker arrangement model. The income or harvest is shared at a ratio of 1:2, with the farmer receiving one-third and the PLP receiving two-thirds. The PLP is expected to set aside one-third of its share for input costs. The PLP labourers are paid slightly less than the market price of labour in the community, but in return they are offered a longer contract duration. It is worth noting that PLP labourers receive around 20 to 40% higher wages than the minimum wage in Ghana.

While we observed that all types of farmers utilise the services of PLPs, it seems that elderly and impoverished farmers are more inclined to engage with PLPs. This was corroborated by a PLP operator in the Ashanti Region who stated, “Mostly, cocoa farmers who are very old and unable to work on their farms, and farmers who lack the financial resources to invest in their farms frequently seek the services of PLPs”.

Based on our assessment of the labour relations and working conditions of the PLP, we argue that this model is likely to alter the horizontal power relations among farmers and workers in Ghana’s cocoa sector. In particular, PLPs can secure higher associational and structural bargaining power compared to hired labourers and Abusa. The findings from our interviews suggest that PLPs and their workers maintain long-term working relationships with farmers. Additionally, PLPs emphasise the capacity development of workers and close collaboration between farmers and workers. These characteristics are associated with a high degree of access to and sharing of labour rights information and possession of high agronomic skills, which are crucial for securing bargaining power.

In addition, PLPs are very cooperative, considering the nature of the organisation, which includes transparency in the partnership and negotiations. Both workers and farmers remain committed, such that PLPs can realistically undertake major strategies for promoting working conditions without the fear that workers will lose their jobs. Such associational and structural power that arises by involving PLPs and their workers more actively in decision-making processes could alter the horizontal power imbalance in the cocoa sector. Though the PLP model primarily focuses on non-migrant labourers, it is important to note that including migrant labourers in the analysis would likely result in similar balance of horizontal power. This assumption is supported by the findings of the bargaining power analysis conducted in informal labour settings, which indicate that the distinction between migrant and non-migrant labourers on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana has minimal impact on horizontal power dynamics.

Sustainability potential and limitations of the PLPs

While considering the sustainability potential and limitations of PLPs, we argue that tensions exist. In general, we can identify the main potential of PLPs in terms of improving investment and productivity, innovation and decent work in Ghana’s cocoa sector. First, cocoa farmers’ poverty persists in Ghana, coupled with inadequate capital for investment in their farming businesses (Fountain and Hütz-Adams 2022). PLPs invest in better production practices to provide higher productivity. Because PLPs make money from higher productivity, there is an inherent incentive to invest more in quality inputs and professionalism. Second, the average cocoa farmer in Ghana is aging and may not be able to easily adopt innovative practices (Bymolt et al. 2018; Fountain and Hütz-Adams 2022). However, there is a popular narrative that young people are more likely to adopt innovative practices in Ghana’s cocoa sector (Anyidoho et al. 2012; Mabe et al. 2021). PLPs recruit young workers who are more likely to understand and adopt innovations on farms. Third, considering the rising concerns about indecent working conditions, such as child labour and poor occupational health and safety in Ghana’s cocoa sector (Fountain and Hütz-Adams 2022; Vigneri et al. 2016; Kissi 2021), the PLP model is likely to promote decent work through availability, affordability and skilled adult labour. While PLPs reduce farmers’ labour costs and the temptation to employ child labour, the model trains workers on health and safety issues and provides personal protective equipment to workers.

Despite their potential for higher innovation, productivity and decent work, the main limitation of PLPs are their limited reach compared to hired labour and Abusa. Our findings show several reasons for the low adoption of PLPs. First, evidence from the study indicates that the end of financial support through RSCs in 2019/2020 hindered the expansion of PLPs to other cocoa-growing areas. As explained by a current PLP operator in the Central Region and a past PLP operator in the Ashanti Region, “Most of the RSCs have stopped because they did not have any sustainable financing plan that could generate further income at the end of the financial grant period”.

Second, our findings indicate that the lack of investment and access to capital is hindering the expansion of PLPs. A PLP operator currently working in the Central Region stated, “Despite receiving numerous requests from farmers to manage their farms, we are unable to accept each acre without additional capital investment, which we do not currently have”.

Third, we also found that the high turnover rate of labourers during the off-season is a major challenge for the sustainability of the PLP model. As noted by a PLP operator in the Central Region, “During the off-season in January and February, when labourers are still engaged in some farm management practices like weeding, we sometimes struggle to pay them due to low income, which causes some of our committed and trained workers to leave, requiring replacements at an additional cost”.

Fourth, we noted in the interviews that COCOBOD’s labour subsidy programmes, such as mass spraying, hand pollination and the issuance of fertilizer subsidies, are obstacles to the expansion of PLPs. Despite the uneven distribution, delay and insufficiency of COCOBOD’s subsidies (Danso-Abbeam and Baiyegunhi 2017; Kolavalli and Vigneri 2018), the knowledge of their existence is a significant disincentive for some farmers who genuinely need to participate in the PLP. Finally, there is a lack of awareness and understanding of the PLP model among farmers, especially regarding the share of income. Most farmers interviewed believe that the PLP model where the farmer only gets one third is not fair and a cause of their disinterest. This lack of awareness and understanding may hinder the adoption and implementation of the PLP model, even where it is available.

We argue that significant investment and access to capital, sesitisation, and education on the benefits of the PLP model are key for addressing the sustainability limitations of PLPs. Indeed, evidence from our study suggests that capital investment particularly, could have a positive impact on PLPs. Our findings show that investment support from various actors to PLPs is important for training, building the capacity of workers and retaining committed workers during the off-season. This would allow PLPs to reach more farmers who are interested in their services and also address the need for improved labour relations and working conditions in Ghana’s cocoa sector.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examined the importance of smallholder farm workers, a group of workers often overlooked in agricultural studies (Riisgaard and Okinda 2018). Our study contributes to the limited discussion on horizontal power dynamics in the smallholder farm context, compared to the many existing studies that focus on plantation work (Bargawi 2015; Gansemans and D’Haese 2020; Riisgaard and Okinda 2018; Selwyn 2007; Thomas 2021).

Beyond family labour, communal labour support and government labour supply, smallholder cocoa farmers employ hired labourers, Abusas’ and PLPs. The labour relations and working conditions of hired labour and Abusa setups reveal an imbalance in horizontal power, which the PLP setup helps to address. In addition, our evidence shows that investment in PLPs is key to their sustainability. By examining various forms of labour supply and the power struggles between smallholder farmers and their workers, our study provides insights that can inform future policy and research on this topic.

In addition to family labour, smallholder cocoa producers often rely on hired labourers and Abusas, who are part of the poorest rural workforce but are often forgotten. Future studies and policy initiatives aimed at addressing labour relations and working conditions on smallholders’ farms must consider these workers. While workers on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana play a crucial role, it is evident that their remuneration, working conditions, and power dynamics are often inadequate and in need of improvement. Therefore, future studies should focus on how workers on smallholder farms can be fully recognised and remunerated in value chains and production networks while also addressing power struggles. This would help to shed light on the power dynamics and struggles of workers in the global economy.

Further, our study reveals that informal labour arrangements continue to play a significant role in cocoa production in Ghana. However, the weak bargaining position of workers in these setups is often due to a lack of access to information and transparency. This has serious implications for the sustainability of Ghana’s cocoa sector. Future policies should focus on reducing information asymmetry in negotiations and partnerships between farmers and workers to improve working conditions and labour relations in informal setups. Moreover, future studies should investigate mechanisms for revealing hidden information in informal labour arrangements. This would enable proper labour supply management and provide workers with the means to address labour rights violations and exploitation in informal negotiations and partnerships. Additionally, future policy consideration should incorporate migrant labourers who have long stay ambitions in cocoa farming within the PLP model, as their inclusion would not significantly impact the horizontal power dynamics.

Our study highlights the potential of PLPs to involve more youths in cocoa farming, which could lead to improved productivity. To encourage youths and landless migrants in PLPs, it is important to strengthen policies and programmes that incentivise their participation. For example, COCOBOD and other local actors could provide working tools and technical advice to youths interested in working on smallholder cocoa farms through PLPs. One successful example of such a programme is the next-generation cocoa youth programme known as MASO, which has promoted the interest of youths in becoming cocoa farmers. By implementing such initiatives, we could help to create a more sustainable future for Ghana’s cocoa sector (Mabe et al. 2021).

Finally, our results also suggest that a lack of investment and capital, and understanding are a major reasons for the lack of expansion of PLPs. To overcome this constraint, various actors along Ghana’s cocoa value chain could come together to create a sustainable financing framework to promote the sustainability of the PLP model. Having such a framework would provide incentives for youths to participate regularly in cocoa farming. In addition, improving farmer–worker relations could help improve the sustainability of the PLP model. Therefore, future empirical enquiries should examine how to promote inclusive and transparent contractual farming arrangements between smallholders and PLPs (Ruml and Qaim 2021). Such studies may provide a better understanding of sharing arrangment and, promote farmers’ interest and trust in the PLP model.

Overall, as various actors in Ghana’s cocoa sector continue to deliberate on action plans to support the labour supply on smallholder cocoa farms, it is essential to recognise that horizontal power is critical to the sustainable supply of labour. Research and policy strategies for each labour supply setup on a smallholder farm should reflect the constraints on labour relations and working conditions in the context of bargaining power.

Notes

-

We interviewed one LBC worker in the Adansi district who had been involved in the implementation of the PLPs. Additionally, we interviewed two PLP operators in the past, one each from the Adansi and Juabeso districts. Further, we interviewed an individual currently operating a PLP and three farmers in the Assin Central Municipal district.

Abbreviations

- COCOBOD:

- The Ghana cocoa board

- GHS:

- Ghana cedi

- LBCs:

- License buying companies

- LSSs:

- Labour supply setups

- PLPs:

- Private labour providers

- RSCs:

- Rural service centers

References

-

Alford, M., S. Barrientos, and M. Visser. 2017. Multi-scalar labour agency in global production networks: Contestation and crisis in the South African fruit sector. Development and Change 48 (4): 721–745.

-

Amanor, K.S. 2010. Family values, land sales and agricultural commodification in South-Eastern Ghana. Africa 80 (1): 104–125.

-

Amfo, B., J.O. Mensah, and R. Aidoo. 2022. Migrants and non-migrants’ welfare on cocoa farms in Ghana: Multidimensional poverty index approach. International Journal of Social Economics 49 (3): 389–410.

-

Amon-Armah, F., N.A. Anyidoho, I.A. Amoah, and S. Muilerman. 2022. A typology of young cocoa farmers: Attitudes motivations and aspirations. The European Journal of Development Research. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00538-w.

-

Anyidoho, N.A., J. Leavy, and K. Asenso-Okyere. 2012. Perceptions and aspirations: A case study of young people in Ghana’s cocoa sector. IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 20–32.

-

Bargawi, H. 2015. Rural institutions in flux: Lessons from three Tanzanian cotton-producing villages. Journal of Agrarian Change 15 (2): 155–178.

-

Barrientos, S. 2014. Gendered global production networks: Analysis of cocoa–chocolate sourcing. Regional Studies 48 (5): 791–803.

-

Barrientos, S. 2019. Gender and work in global value chains: Capturing the gains? Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

-

Barrientos, S., and K. Asenso-Okyere. 2009. Cocoa value chain: Challenges facing Ghana in a changing global confectionary market. Journal Fur Entwicklungspolitik 25 (2): 88–107.

-

Barrientos, S., G. Gereffi, and A. Rossi. 2011. Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. International Labour Review 150 (3–4): 319–340.

-

Bernstein, H. 2011. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change: Agrarian Change and Peasant Studies. Halifax: Fernwood.

-

Bymolt, R., A. Laven, and M. Tyzler. 2018. Demystifying the cocoa sector in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Amsterdam: The Royal Tropical Institute (KIT).

-

Carswell, G., and G. de Neve. 2013. Labouring for global markets: Conceptualising labour agency in global production networks. Geoforum 44: 62–70.

-

Coe, N.M., and D.C. Jordhus-Lier. 2011. Constrained agency? Re-evaluating the geographies of labour. Progress in Human Geography 35 (2): 211–233.

-

Contzen, S., and J. Forney. 2017. Family farming and gendered division of labour on the move: A typology of farming-family configurations. Agriculture and Human Values 34 (1): 27–40.

-

Danso-Abbeam, G., and L.J.S. Baiyegunhi. 2017. Adoption of agrochemical management practices among smallholder cocoa farmers in Ghana. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development 9 (6): 717–728.

-

Dzanku, F.M., and D. Tsikata. 2022. Implications of socioeconomic change for agrarian land and labour relations in rural Ghana. Journal of Rural Studies 94: 385–398.

-

Fold, N., and J. Neilson. 2016. Sustaining supplies in smallholder-dominated value chains: Corporate governance of the global cocoa sector. In The Economics of Chocolate, 195–212. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

-

Gansemans, A., and M. D’Haese. 2020. Staying under the radar: Constraints on labour agency of pineapple plantation workers in Costa Rica? Agriculture and Human Values 37 (2): 397–414.

-

GSS. 2014. Ghana Living Standard Survey Round 6 (GLSS 6): Poverty Trends in Ghana 2005–2013. Accra, Ghana. http://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/Living%20conditions/GLSS6_Main%20Report.pdf. Accessed 24 January 2019.

-

Gyapong, A.Y. 2021. Land grabs, farmworkers, and rural livelihoods in West Africa: Some silences in the food sovereignty discourse. Globalizations 18 (3): 339–354.

-

Hill, P. 1961. The migrant cocoa farmers of Southern Ghana. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 31 (3): 209–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/1157262.

-

Hill, P. 1997. The Migrant Cocoa-Farmers of Southern Ghana: A Study in Rural Capitalism. Oxford: James Currey Publishers.

-

Kissi, E. A. 2021. Governance for Decent Work in Agricultural Globalisation. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Kassel, Germany.

-

Kissi, E.A., and C. Herzig. 2020. Methodologies and perspectives in research on labour relations in global agricultural production networks: A review. The Journal of Development Studies 56 (9): 1615–1637.

-

Kolavalli, S., and M. Vigneri. 2018. The cocoa coast: The board-managed cocoa sector in Ghana. Intl Food Policy Res Inst.

-

LeBaron, G., and E. Gore. 2020. Gender and forced labour: Understanding the links in global cocoa supply chains. The Journal of Development Studies 56 (6): 1095–1117.

-

Lewis, S. 2015. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Health Promotion Practice 16 (4): 473–475.

-

Louche, C., L. Staelens, and M. D’Haese. 2020. When workplace unionism in global value chains does not function well: Exploring the impediments. Journal of Business Ethics 162 (2): 379–398.

-

Mabe, F.N., G. Danso-Abbeam, S.B. Azumah, N.A. Boateng, K.B. Mensah, and E. Boateng. 2021. Drivers of youth in cocoa value chain activities in Ghana. Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies 11 (4): 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-10-2019-0177.

-

Masamha, B., V. Thebe, and V.N.E. Uzokwe. 2018. Mapping cassava food value chains in Tanzania’s smallholder farming sector: The implications of intra-household gender dynamics. Journal of Rural Studies 58: 82–92.

-

Mohan, S. 2016. Institutional change in value chains: Evidence from tea in Nepal. World Development 78: 52–65.

-

Morgan, J., and W. Olsen. 2011. Aspiration problems for the Indian rural poor: Research on self-help groups and micro-finance. Capital & Class 35 (2): 189–212.

-

Mukhamedova, N., and R. Pomfret. 2019. Why does sharecropping survive? Agrarian institutions and contract choice in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. Comparative Economic Studies 61 (4): 576–597.

-

Oya, C. 2012. Contract farming in sub-Saharan Africa: A survey of approaches, debates and issues. Journal of Agrarian Change 12 (1): 1–33.

-

Padmanabhan, M.A. 2007. The making and unmaking of gendered crops in Northern Ghana. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 28 (1): 57–70.

-

Pettas, D. 2019. Power relations, conflicts and everyday life in urban public space: The development of ‘horizontal’power struggles in central Athens. City 23 (2): 222–244.

-

Phillips, N. 2011. Informality, global production networks and the dynamics of ‘adverse incorporation.’ Global Networks 11 (3): 380–397.

-

Raynolds, L.T. 2014. Fairtrade, certification, and labor: Global and local tensions in improving conditions for agricultural workers. Agriculture and Human Values 31 (3): 499–511.

-

Riisgaard, L., and O. Okinda. 2018. Changing labour power on smallholder tea farms in Kenya. Competition & Change 22 (1): 41–62.

-

Rizzo, M. 2013. Informalisation and the end of trade unionism as we knew it? Dissenting remarks from a Tanzanian case study. Review of African Political Economy 40 (136): 290–308.

-

Ruml, A., and M. Qaim. 2021. Smallholder farmers’ dissatisfaction with contract schemes in spite of economic benefits: Issues of mistrust and lack of transparency. The Journal of Development Studies 57 (7): 1106–1119.

-

Schmalz, S., C. Ludwig, and E. Webster. 2018. The power resources approach: Developments and challenges. Global Labour Journal. https://doi.org/10.15173/glj.v9i2.3569.

-

Schuster, M., and M. Maertens. 2017. Worker empowerment through private standards. Evidence from the Peruvian horticultural export sector. The Journal of Development Studies 53 (4): 618–637.

-

Selwyn, B. 2007. Labour process and workers’ bargaining power in export grape production, North East Brazil. Journal of Agrarian Change 7 (4): 526–553.

-

Selwyn, B. 2009. Labour flexibility in export horticulture: A case study of northeast Brazilian grape production. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (4): 761–782.

-

Silver, B.J. 2003. Forces of Labor: Workers’ Movements and Globalization Since 1870. Cambridge University Press.

-

Silverman, D. 2017. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook, 5TH ed. London: Sage.

-

Thomas, H. 2021. A ‘Decent Cuppa’: Worker power and consumer power in the Sri Lankan tea sector. British Journal of Industrial Relations 59 (1): 114–138.

-

Thompson, D. 2021. Building and transforming collective agency and collective identity to address Latinx farmworkers’ needs and challenges in rural Vermont. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (1): 129–143.

-

Torvikey, G.D. 2021. Reclaiming our land and labour: Women’s resistance to extractivist agriculture in Southeastern Ghana. Feminist Africa 2 (1): 49–70.

-

van Hear, N. 1984. ‘By-day’boys and dariga Men: Casual labour versus Agrarian capital in Northern Ghana. Review of African Political Economy 11 (31): 44–56.

-

van Rijn, F., R. Fort, R. Ruben, T. Koster, and G. Beekman. 2020. Does certification improve hired labour conditions and wageworker conditions at banana plantations? Agriculture and Human Values 37 (2): 353–370.

-

Wright, E.O. 2000. Working-class power, capitalist-class interests, and class compromise. American Journal of Sociology 105 (4): 957–1002.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development for providing funding for this research through the exceed programme of the German Academic Exchange Service. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the International Center for Development and Decent Work for their financial support in conducting the study. The authors would also like to extend their appreciation to the reviewers for their valuable feedback on the earlier version of the manuscript, which greatly contributed to its improvement.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kissi, E.A., Herzig, C. Labour relations and working conditions of workers on smallholder cocoa farms in Ghana. Agric Hum Values (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-023-10470-2

- Accepted

- Published

- DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-023-10470-2

- Implications of Governance Factors for Economic and Social Upgrading in Ghana’s Cocoa Value Chain - February 27, 2024

- Labour Relations and Working Conditions of Workers on Smallholder Cocoa Farms in Ghana - January 18, 2024

- Expand Value Addition To Ghana’s Cocoa Beyond The Idea Of Chocolate - July 5, 2021