An Economic Lens Is Needed To Eradicate Child Labour In West African Cocoa Sector

No less than three layers will have to be peeled off to get to the core of work of children in the West African cocoa sector.

Terminology can harm, confuse, mislead and can destroy markets. That is why a fair representation of the labour issues in West African cocoa landscapes is important.

Dismantling the existing framing on child labour requires a deeper understanding of farming realities. Having a clear contextual understanding of the systemic characteristics will be the starting point for a transformation of the challenging labour situation in this sector.

First, demystifying implies moving away from the slavery discourse in markets.

Secondly, rejecting the so-called modern slavery framing as not being helpful, and thirdly moving away from superficial child labour analyses, finally understanding the socio-economic reality in cocoa family farming in West Africa, being predominantly assistance of children to their parents.

Let’s do the peeling off exercise. Infusing optimism for change.

SLAVERY

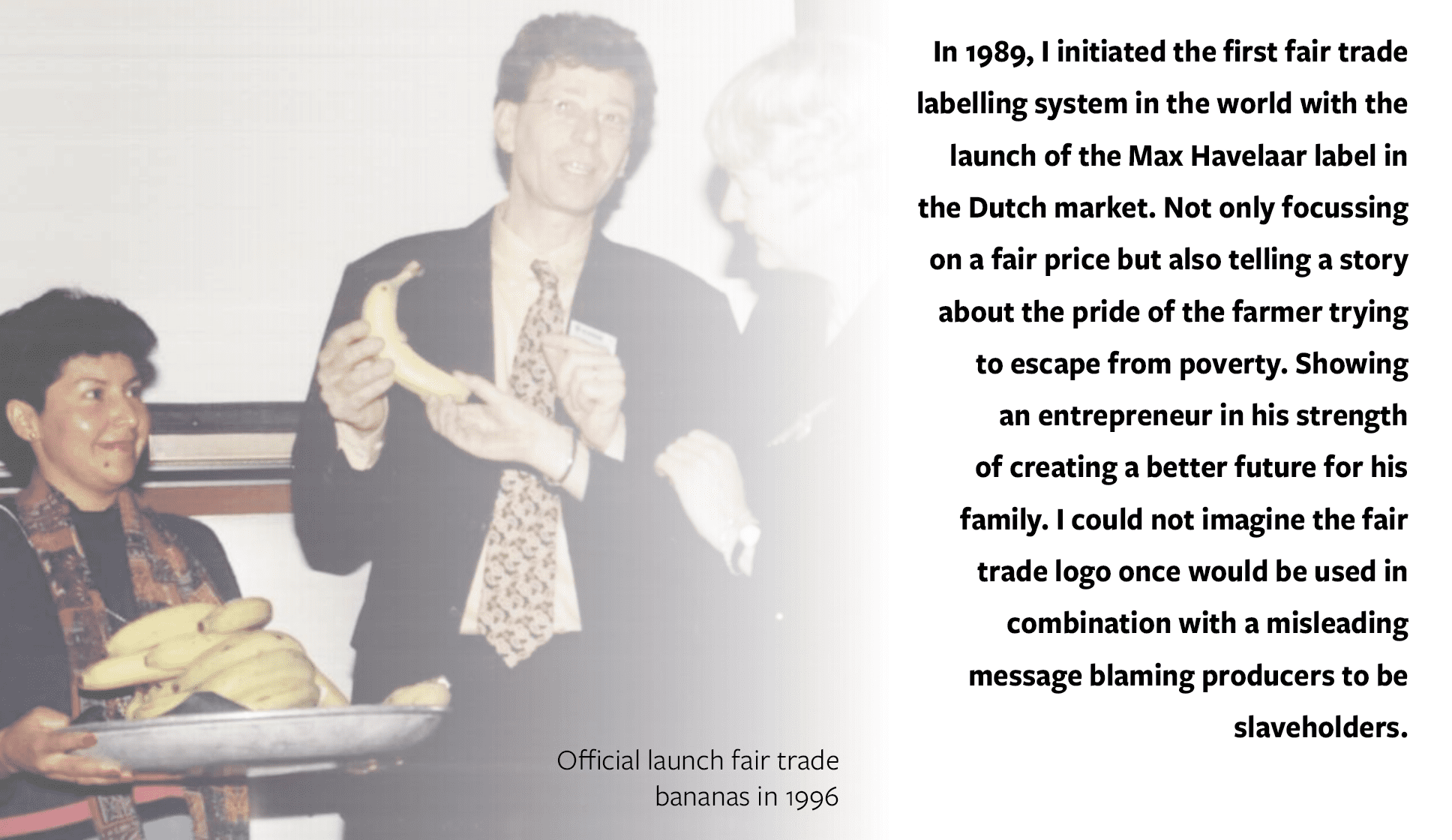

Traditional anti-slavery activists recently got support from so-called ‘slave free’ marketers using the ‘broken chain’ logo promoting fair trade chocolate in Western consumer markets.

Actually, the Dutch brand Tony’s Chocolonely is making an international breakthrough by framing cocoa from West Africa as structurally linked to child slavery.

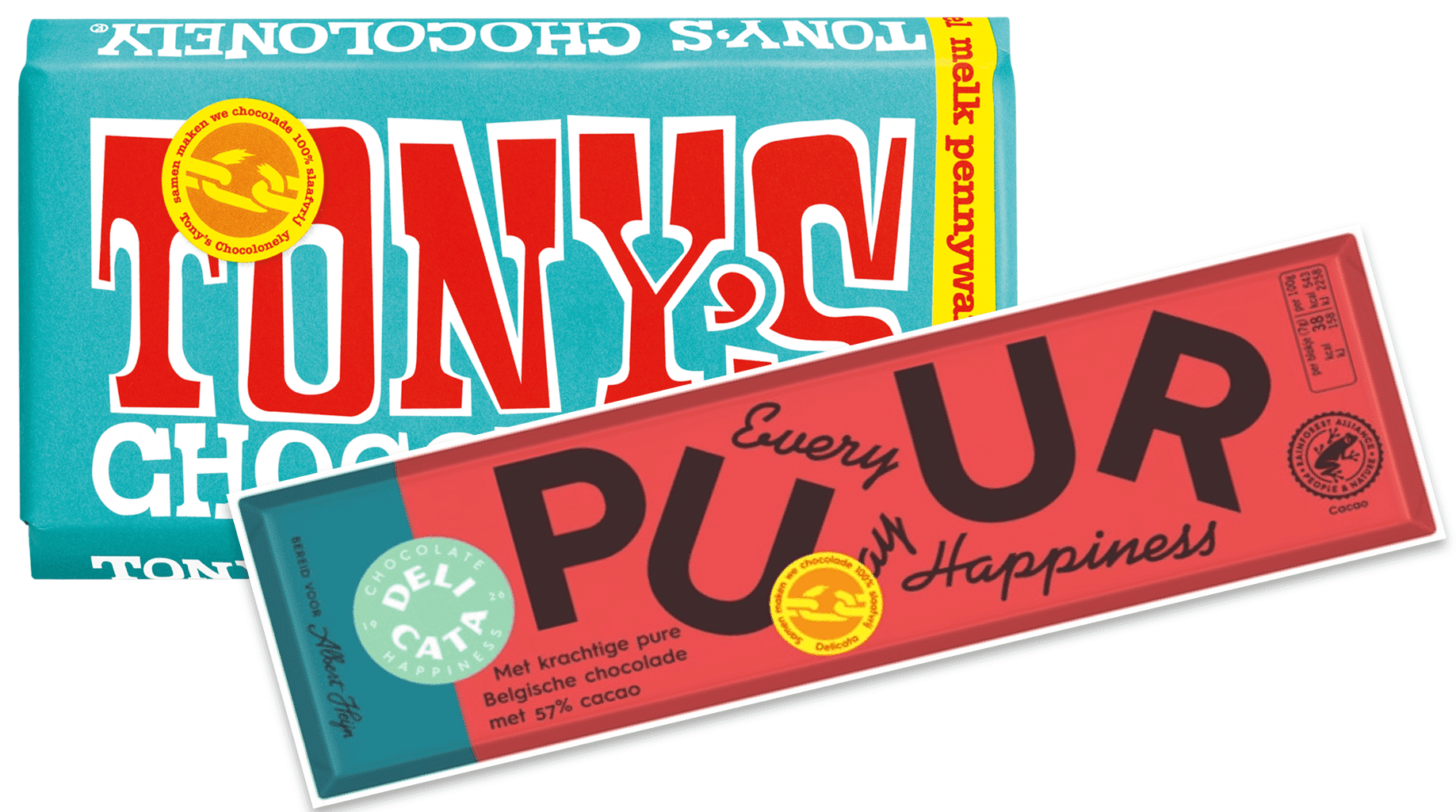

Recently the Dutch retail giant AholdDelhaize has put the logo on Delicata, their private chocolate label, too.

Always disapproving of political statements, this move has escaped the attention of corporate management, I assume.

The negative slavery framing by Tony’s has been done without any sensitivity to the historical context.

For West Africans, slavery is linked to the dramatic period of the intercontinental slave trade.

All school children are once visiting the slave forts at the coast and the imprint in their brains is the understanding of a reality in which black lives did not matter at all.

Using the ‘broken chain logo’, symbolising the liberalisation of this worst form of racism, slavery allegations related to cocoa production is shocking to them.

‘My parents are no slaveholders; African parents also love their children’ is a reaction of a farmer in Cote d’ Ivoire which is an imprint in my memory.

MODERN SLAVERY

While using the ‘slave free’ logo in direct consumer communication on the shelves, the legitimisation of this message on Tony’s website is related to the more complex concept of modern slavery.

So, the slavery framing is presented with more nuances, switching to a discourse about modern slavery.

Linking historic slavery symbols to a modern slavery discourse is confusing and effectively misleading consumers.

Modern slavery is a container word covering different types of slavery: like forced labour, sex trafficking, bonded labour and recruitment of child soldiers.

The common denominator is the presence of violence and intimidation. All these types are very harmful but very different in character.

Bringing them under one denominator is not useful for finding tailor-made solutions for each type. The loaded word ‘slavery’ does not help.

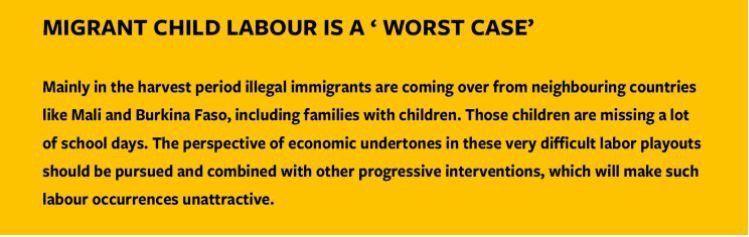

In West African cocoa research the number of so-called modern child slavery cases is estimated at a level of 30,000 in a sector with 1.4 million to 1.8 million cocoa farm households offering employment to over 3.5 – 4.0 million people.

Though 30,000 is only a fraction of the number of child labourers, the forced nature of the labour makes it a particularly grave concern.

However, it is important to highlight the fact that relatively low figures cannot be used to represent a system-wide characteristic of a whole sector.

Justifying a generic slavery framing in the market with this seems irresponsible to me. Framing, which hurts people.

Let’s take a closer look at this figure of 30,000 cases of so-called modern slavery. The figure comes from the report ‘Bitter sweets’, from Tulane University.

However, a section in the report shows some important caveats on limitations associated with the figures mentioned, that it should be used with caution.

The Tulane report highlighted that “the projected estimates of children and adults in forced labour in the cocoa sector of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana are based on very few identified cases. Due to the small numbers, the estimates are less precise, and should be interpreted with caution”.

All in all, the 30,000 figure of modern slavery cases seems to be a weak foundation for strong market messages, which have far-reaching reputational damage to vulnerable cocoa farmers.

Most probably Tony’s is aware of that and for this reason, their storyline makes a second turn, presenting data about child labour, underpinning an opportunistic messaging about (modern) slavery.

In general, researchers are reluctant using concepts as slavery or modern slavery and prefer to focus their studies on child labour, being a systemic issue and a well-defined category with references to ILO standards and national interpretations.

So child labour is the real debate with some real data-based references.

CHILD LABOUR

Research has shown at least two interesting facts:

One: The vast majority of work done by children is done on their parents’ farms, and the demographics show that most children in the study were from families of smallholder farmers, who are conducting farming activities as part of their household’s normal economic activity.

A careful contextualisation of these facts could largely indicate that most of the reported cases of child labour have to be understood as the assistance of children to their parents and constitute part of the culture of socialising, learning and general education in life skills, rather than exploitation.

Which effectively means that, like any other labour activity, hazards which could be linked to that engagement should be managed and de-risked.

This is also why working children are allowed under ILO standards, with time restrictions and avoiding risky tasks.

Worst cases of child labour – when working hours have been exceeded and hazards are not managed- is an issue of high concern and require direct action.

Two: the number of children who are attending primary school is growing. For Ghana, 96% and for Côte d’Ivoire, 80%.

Numbers for secondary schooling are also increasing. The progressive development of formal education suggests the severity of child work is decreasing, at least in the number of working hours. Child labour, where children get no access to adequate education, is future-destroying.

The other aspect of child labour that destroys the future of a child is carrying heavy loads, risky workload overtasking the physical capacities of growing children.

The ILO hazardous labour protocol is clearly defining the different aspects. The persistent high figures of child labour – often teenagers – are mainly related to these activities which are indeed worrying.

Carrying heavy loads, exposure to agro-chemicals and the use of sharp tools are the main risk factors.

However, to understand these elements we have to understand everyone’s work at a cocoa farm.

Also, adult workers are exposed to these risks. There is nothing easy about making sure everyone has enough nutritious food, clean water, good health, and time for learning and leisure.

Demands on women are unrealistic. For the many single women running households, the dual responsibility of domestic work and income generation can be overwhelming.

In other households, the adults are too old, or physically unable, to do the necessary work. Community work is quite demanding. Is it any wonder, then, that children are often asked to help?

The line between these domestic chores and income-generating work is often blurred.

All these tasks have the potential for harm, which is increased when adults cannot supervise. Surrounding all these circumstances is the unceasing labour of rural life – the context of child work.

These challenges mentioned here are not to downplay anyone overworking including children.

Issues defined in the ILO 182 hazardous labour protocol can only be addressed when working conditions in general for all workers of all ages are improved. This includes reduced and more safe use of chemicals, mechanical equipment for transport and for weeding and processing cocoa pods.

The context of children working is assistance to their parents.

The context of children working as assistance to their parents is a challenging context; making a contribution as a child to survive as a family.

That’s a heavy burden for a child or teenager, till 18 years, according to the official child labour definitions.

You would like to give a child a more carefree starting position in life. At the same time for many children, it is a safe environment being at the farm of caring parents.

A huge difference with the child labour context of exploitation is understood as the greed of entrepreneurs misusing vulnerable children as hired labour for higher profits.

Terrifying examples of this exploitation are found in large scale agriculture, mining and industry.

AN ECONOMIC LENS

Taking an economic lens is crucial for finding workable and effective solutions. The key question is of course: Who else can perform the assistance children offer their parents now?

Who else can do the work now done by children and teenagers?

If the farmer could afford hired labour and offer them a decent working place it would surely be his and her preference. However, hired labour is too expensive and in some instances, labour is unavailable.

Minimum wages are often higher than what the cocoa farmer can afford given his low income. Moreover, from the perspective of an adult worker, a professional career as an agricultural labourer is not too attractive.

Given the labour intensive nature of current cocoa farming, the youth have understandably shy away from the sector.

Growing your children is about values; the eradication of child labour is about value creation.

Historically, all over the world, the eradication of child work is linked to a process of modernization of labour in agriculture in combination with a number of key elements:

- hiring permanent and seasonal workers

- mechanisation replacing labour

- agri-service provision businesses

Of these innovations, service provision turned out to be the most promising concept offering the latest technology, time-bound high-quality professionals and (cost) efficient services in peak times.

Higher farmer incomes are the decisive preconditions for these innovations in the field of labour. Innovations which could end child work.

From a broader perspective, science shows that a higher farmer income is dependent on six main factors, moving from farming by default to agricultural entrepreneurship: Farm size, Cost of production, Yield, Price, Diversification and Market Linkages.

This historic experience is challenged by the sustainability agenda of our times and by consequence we have to reinvent this agenda of six decisive factors.

Neglecting one of these aspects will not result in positive effects for farmers and society.

Both an agroforestry and agroecology concept for the cocoa sector have to be explored to define a sustainable future solving social and environmental issues supported by new economic realities.

There are no cocoa farmers; just farmers with the potential to serve different markets with a range of products.

The inclusive and sustainability agenda could be summarized in six interventions:

- Farm size: scaling up from subsistence to commercial farming, from maximization with high cost to optimisation with societal and environmental return.

- Cost of production: efficiency through science and technology, internalisation of social and environmental costs.

- Yield: optimal return per hectare through sustainable intensification

- Price: more balanced supply chains – reducing oversupply- payments for environmental services.

- Diversification: serving different markets with a range of products. Local and regional. Infrastructure for transport and cooling, freezing, drying and processing and retail are well developed.

- Market linkages: from loose to tight value chains, access to finance, science & technology.

In conclusion, the balance of 30 years of interventions is poor. Controlling made child labour more hidden, but no less prevalent. Economic incentives for innovations were weak.

Promises from the world of big businesses have reached discouragingly low levels. Not a single promise kept. A new agenda from an economic lens has to become the leading beam of light.

Prioritizing economic transformation is crucial for eliminating the work of children. This is even more important because currently, irresponsible framing around this topic confuses consumers, businesses and policy makers alike.

An example of proposed counter effective policies is the recently published documents of the European Commission on due diligence measures with a focus on child labour lacking the economic lens and provoking de-risking instead of solving critical issues.

A heavy reporting burden for farmers and businesses could turn out to be a waste of time and money.

Without a business case for innovations cheating the auditor is around the corner. A farmer needs a doctor, no policeman.

In a poverty context positive changes require an improved earning model for farmers based on six interconnected interventions.

During the last week of July, I paid an exciting visit to Ghana, kindly hosted by Solidaridad’s West Africa team. A part of the programma was a Roundtable conference on recent developments in the cocoa sector. This article is a reflection on the outcomes of this multi-stakeholder meeting. A strong coalition for change growing.

A PLEA FOR FARMER KNOWLEDGE

Understanding labour realities in the cocoa sector was a challenge for me. The scientific and policy frameworks are (over) complicated.

A lot of studies are needed to understand the different frameworks and contexts. The logic behind the ILO standards and the national interpretations.

The hazardous work protocol, components of child labour that relate to exploitation as against hazards, clear indicators that differentiate between child labour, light work, child work and house chores and the related hazards, the age-appropriate categories, conditional and unconditional worst forms, the different monitoring and remediation systems etc.

In most instances, the question that is being asked is, how child labour has been understood to be “exploitation”, but its components also include hazards.

There are hazards with many tasks, even those that are deemed to be acceptable such as child work, light work and house chores.

Hazards and exploitation present different contexts for addressing them, if we really need to eliminate unethical labour issues in cocoa.

Indeed, there is the need for an intellectual discussion around this including voices from producing countries.

The often quoted reports are standard reading. American studies (Tulane University and NORC) are dominant in framing the issues, while I have learned more from the less quoted ‘Demystification’ study of the Tropeninstitut in The Netherlands.

Powerful marketing of science is all about becoming an influencer. The regularly updated Cocoa Barometer is a masterpiece.

Moreover, I have learned a lot from articles like that of Kristy Leissle, a life time field worker, with the title ‘ To understand child labor, we need to understand everyone’s labor” presenting the daily realitiy of farming adequately.

However, my most important learnings came from exchanges with Solidaridad’s West Africa staff of local experts running innovative programmes in the sector.

And even more importantly from exchanges with local partners and farmers, their wives and children.

They don’t care so much about definitions and protocols. Intuitively they understand the realities of child work, as assistance to parents in an informal economy, and not the case of parents exploiting their children.

They realize using the word child labour could be confusing; parents don’t offer a labour contract, there are no payments, no trade union to join, no time writing or compensation of overtime.

Just working to survive as a family. And if in pursuing survival, hazards occur, that is very different from an exploitative parent.

Recorded notes from my conversations during my recent visit to Ghana are farmer wisdom; some quotes worthwhile to share:

‘Don’t portray us, farmers, as irresponsible; we are trying to survive in a poverty context’, is a key message.

‘Of course, we as farmers understand that we have to de-risk the work our children are doing. However we dream about the possibility of attracting hired labour or to have a small transporter for carrying heavy loads. This will minimise the risks and hazards our children face, as they socialise through farm work, and gain some useful life skills for their future’

A farmer shared with me that, ‘Me, as a father, I have appreciated that my teenage son teaches me how to use agrochemicals in a safe way and how to wear protective clothing. After all, only my son can read the instructions’.

If farmers understand the risks some farm activities pose to their children, they will minimize its effects on their children.

‘Urban people do not understand that a sharp knife is less dangerous than a blunt one. That does not mean that we accept the existing level of injuries. Manual work comes with risks and we can reduce them.

Finally, mechanisation will improve the situation; there is no other structural solution’. This discussion on labour, should therefore include alternatives for laborious manual farm work. A ‘right based approach’ – just claiming rights – will not help.

‘Working with your children is a part of education. Learning about the hard life they will be facing as adults. It is teaching them about responsibilities and skills to survive. Even some of our children will become the farmers of the future.’

‘I don’t really understand and appreciate the complexities of NGO jargon and policy frameworks. I don’t feel the connection with my daily realities; In fact these concepts exclude farmers from the debate about our own future.’

Local experts shared their appreciation for programmes addressing critical issues relating to farming. ‘But the outreach of NGO programmes is limited to no more than 10% of the production zones; no continuity, no scale’.

Perhaps the strongest message is the local understanding of the ‘manipulation of the debate’ focussing on child labour, the weakest actor. ‘As long as we are debating child labour as the first topic of importance the critical role of trading companies, disfuctinal markets, governments and consumers do not get the attention they deserve.’

I am a son of Dutch farmer; growing tulips of course. Nowadays, the work I did on the farm, fifty years ago, will be classified as “worst case of child labour, Something wrong with the definitions? “.